Mrs. Waitaminnit—The Woman Who Is Always Late: George Herriman’s First Daily Strip?

What was George Herriman’s first daily comic strip? Even though Herriman is acknowledged by many artists and critics as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, cartoonists to ever work in the art form, it turns out that there still is not a straightforward answer to that question. In his article from 1983 titled “The Forgotten Years of George Herriman,” Bill Blackbeard wrote:

While I was researching the 1903 World Series in the Evening World using the Library of Congress’s excellent digital collection of newspapers Chronicling America, I stumbled on a page of comics following the sports section. And a strip called Mrs. Waitaminnit—the Woman Who Is Always Late, to my surprise, was signed “Geo. Herriman.” I checked the issues of the newspaper before and after and determined that there were twenty-two episodes of this comic strip from September 15, 1903 to October 13, 1903. Excepting the second episode, they were all authored by Herriman. I had never heard of Mrs. Waitaminnit before. The authors of Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman wrote that Herriman’s first weekday strip was Home Sweet Home which had four episodes in February and March 1904 (probably favoring the term weekday over daily because the episodes weren’t consecutive). Bill Blackbeard identified Herriman’s first daily to run more than a week (a total of ten episodes) as Mr. Proones the Plunger, which ran from December 10, 1907 until December 26, 1907. Mrs. Waitaminnit predates both Home Sweet Home and Mr. Proones the Plunger and covers a longer period, so it’s now the earliest daily we know of by Herriman. His first daily? Maybe… but I wouldn’t be surprised if more turn up. In fact, there are a few one-shot and two-shot comic strips that appear in early 1903 in the same paper.

One more observation I can’t resist: a black cat with a ribbon, which made its first appearance in Herriman’s Sunday supplement Lariat Pete, appears in the later episodes of this series.

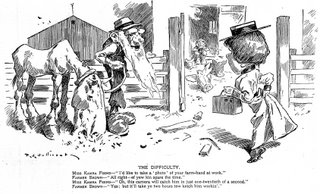

Below are all of the episodes of Mrs. Waitaminnit. They include the one episode not by Herriman, as well as a comic strip by Herriman called Little Tommy Tattles which was substituted for two episodes. They are from the Evening World, downloaded from the Library of Congress website Chronicling America. The images of this newspaper were provided to the Library of Congress by the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundation.

It has now become evident that research into the classic period of the American comic strip, a still considerably obscure era between 1896 and 1930, will not be completed until the files of every American newspaper of any sizable circulation in that general time has been examined… Even in the instances of those cartoonists who have been considered of major rank for a great many years… there may well be extraordinary surprises in store for the assiduous researcher. (NEMO: The Classics Comics Library, June 1983)I had one of those extraordinary surprises last week, but the research that uncovered it was more serendipitous than assiduous.

While I was researching the 1903 World Series in the Evening World using the Library of Congress’s excellent digital collection of newspapers Chronicling America, I stumbled on a page of comics following the sports section. And a strip called Mrs. Waitaminnit—the Woman Who Is Always Late, to my surprise, was signed “Geo. Herriman.” I checked the issues of the newspaper before and after and determined that there were twenty-two episodes of this comic strip from September 15, 1903 to October 13, 1903. Excepting the second episode, they were all authored by Herriman. I had never heard of Mrs. Waitaminnit before. The authors of Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman wrote that Herriman’s first weekday strip was Home Sweet Home which had four episodes in February and March 1904 (probably favoring the term weekday over daily because the episodes weren’t consecutive). Bill Blackbeard identified Herriman’s first daily to run more than a week (a total of ten episodes) as Mr. Proones the Plunger, which ran from December 10, 1907 until December 26, 1907. Mrs. Waitaminnit predates both Home Sweet Home and Mr. Proones the Plunger and covers a longer period, so it’s now the earliest daily we know of by Herriman. His first daily? Maybe… but I wouldn’t be surprised if more turn up. In fact, there are a few one-shot and two-shot comic strips that appear in early 1903 in the same paper.

One more observation I can’t resist: a black cat with a ribbon, which made its first appearance in Herriman’s Sunday supplement Lariat Pete, appears in the later episodes of this series.

Below are all of the episodes of Mrs. Waitaminnit. They include the one episode not by Herriman, as well as a comic strip by Herriman called Little Tommy Tattles which was substituted for two episodes. They are from the Evening World, downloaded from the Library of Congress website Chronicling America. The images of this newspaper were provided to the Library of Congress by the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundation.